On Thursday, September 12, Dr. Paul Spitzer ‘68 gave a talk titled “Lessons From the Osprey Gardens” to mark the first day of his monthlong stay at Wesleyan. Dr. Spitzer is a visiting guest who will be giving several talks over the course of his stay and leading field trips for Mike Singer’s BIOL220/ Conservation Biology class. His next seminar—Biological Secrets & Ecological Significance of the Common Loon—will take place on Thursday, October 3 at noon here at Wesleyan.

On Thursday, September 12, Dr. Paul Spitzer ‘68 gave a talk titled “Lessons From the Osprey Gardens” to mark the first day of his monthlong stay at Wesleyan. Dr. Spitzer is a visiting guest who will be giving several talks over the course of his stay and leading field trips for Mike Singer’s BIOL220/ Conservation Biology class. His next seminar—Biological Secrets & Ecological Significance of the Common Loon—will take place on Thursday, October 3 at noon here at Wesleyan.

Spitzer studied under renowned naturalist Roger Tory Peterson before completing a PhD in osprey studies at Cornell. His career has been dedicated to osprey restoration and protection, and now that the East Coast populations are relatively stable, Spitzer has focused his work on ecosystem management to ensure that populations of menhaden fish, the osprey’s main food source, are in abundance.

- Please note: Field trips are open to interested members of the Wesleyan community. Please email Mike Singer (msinger@wesleyan.edu) for more information.

Spitzer’s home bases are two osprey “gardens,” sanctuaries where ospreys have proliferated: The first is Great Island Wildlife Area in Old Lyme, Connecticut, which boasts some 30 ospreys across 500 acres; the second is Gardiners Island, between the forks of Long Island, New York, home to New York’s largest colony of ospreys. He describes them as his “bioregions,” home-base regions or species that he says all field scientists have–the places that they “return to when [there are] new questions to ask.”

Spitzer’s talk focused on the history of osprey restoration and the relationship of those two gardens’ populations with menhadens. In addition to being commanding birds of prey, ospreys are a bioindicator, a species that can inform scientists on the qualitative status of their environment; studying the size and health of osprey populations can lead researchers to conclusions about the conditions of their prey, competitors, and inanimate factors in their ecosystems. After the introduction of commercial-use DDT, a chemical insecticide, in 1945, the osprey populations of the East Coast saw steadily decreasing numbers, a warning bell for the health of their ecosystems.

DDT builds up in the animals that ingest it, meaning that birds of prey like the osprey, which eat large amounts of these contaminated fish, are found with huge accumulations of the chemical in their system. This process by which DDT rises through the food chain to accumulate in predators is called biomagnification. The most devastating effect of DDT on ospreys was thinning their eggshells–even a mother osprey nesting over her eggs could crack the fragile shells and kill the hatchling within. With nests averaging 2.5 hatchlings per brood, even one lost egg per nest had brutal consequences on population size. Though upsetting, Spitzer recalls this discovery being “the best thing that could have happened,” because the case against DDT needed “clear indicators” of the damage it caused. His research on its effects on osprey eggs was a major step towards the chemical’s ban in 1972.

DDT builds up in the animals that ingest it, meaning that birds of prey like the osprey, which eat large amounts of these contaminated fish, are found with huge accumulations of the chemical in their system. This process by which DDT rises through the food chain to accumulate in predators is called biomagnification. The most devastating effect of DDT on ospreys was thinning their eggshells–even a mother osprey nesting over her eggs could crack the fragile shells and kill the hatchling within. With nests averaging 2.5 hatchlings per brood, even one lost egg per nest had brutal consequences on population size. Though upsetting, Spitzer recalls this discovery being “the best thing that could have happened,” because the case against DDT needed “clear indicators” of the damage it caused. His research on its effects on osprey eggs was a major step towards the chemical’s ban in 1972.

Nurturing osprey habitats requires stable populations of fish for them to feed on, especially the menhaden. “Relationships in nature are incredibly particular,” Spitzer remarked on the correlation between the menhaden surge after DDT was banned and the reflourishing of ospreys. “The post-DDT ‘break even point’ is fairly low for ospreys, so they’ve been able to proliferate in New York and Connecticut.” Initial restoration strategy for the ospreys also involves the installation of nesting platforms, which are wooden poles several meters high that give ospreys a nesting perch safe from ground predators. Spitzer relates the menhaden’s importance to the health of not only ospreys, but bald eagles and the common loon as well, stating that the fish are crucial to the health and services of the ecosystem as a whole.

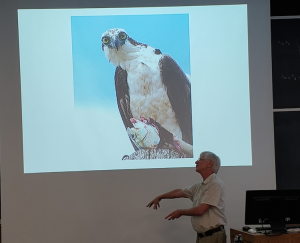

Spitzer’s talk also touched on the importance of “citizen scientists,” members of the communities where the osprey gardens are located who volunteer their time, energy, and passion for scientific projects. “Virtually every project I’m involved with now includes citizen scientists,” Spitzer said, mentioning photographers, birdwatchers, volunteers to build nesting platforms, and more. He continued on to detail the metrics by which osprey population health is measured, including mean brood size and number of young/active nests. “There’s always more about them to be learned,” Spitzer said to the audience, while on the screen behind him an osprey, mid-flight, grasped a menhaden in its talons.